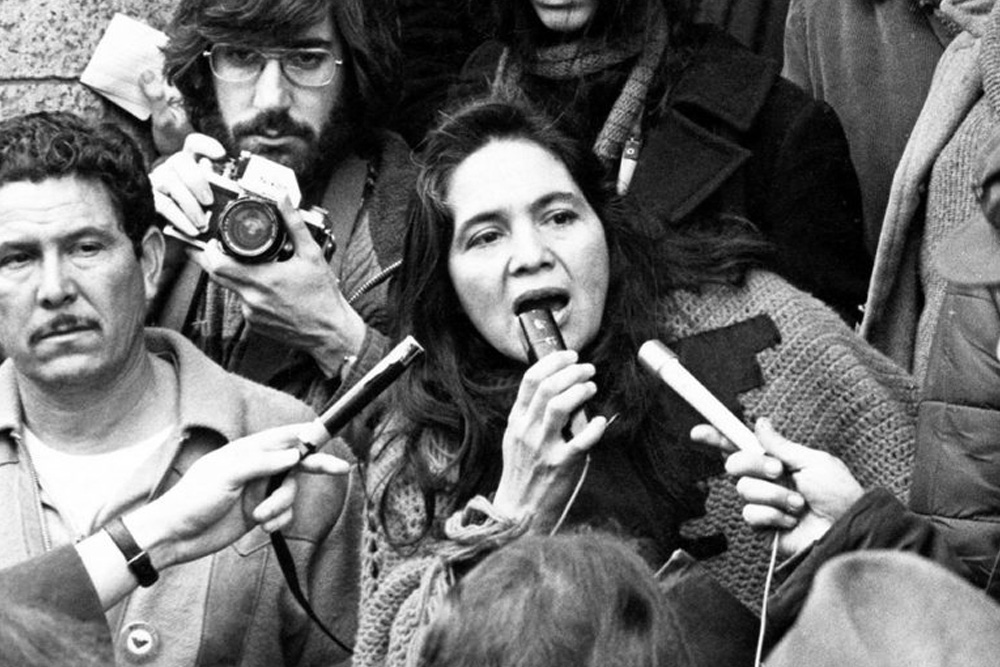

Today is a special day in history: the birthday of labor activist Dolores Huerta.

Huerta, who was born April 10, 1930, grew up with a mother who set a strong example of community activism. After working multiple jobs, Alicia Chávez bought her own restaurant and hotel. She hosted low-paid farmworkers at affordable rates, even waiving their accommodation fees at times. Alicia Chávez also modeled integration as the agricultural community. Where they lived was made up of Mexican, Filipino, African American, Japanese, and Chinese families.

Although Huerta studied to become a teacher, she soon left the profession because she was tired of seeing her students, many the children of low-income farm workers, come to school hungry and lacking proper clothing.

The Power of Community Organizing

After leaving teaching, Huerta worked with the Stockton (Calif.) Community Service Organization and founded the Agricultural Workers Association. She soon met César E. Chávez, and they co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) to help give agricultural workers the power to band together and receive better treatment. The NFWA is currently known as United Farm Workers (UFW).

She successfully lobbied legislators to get Aid for Dependent Families and disability insurance protection for farm works in California. Huerta also helped enact 1975’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act, the first law in the U.S. that allowed farm workers to organize and bargain for better working conditions and wages.

Committing to Women’s Rights

While organizing the first national boycott of grapes, Huerta became involved with the women’s liberation movement. She saw how well the goals of women’s liberation and worker’s rights were and began working for women’s rights within the agricultural worker community. She fought against gender discrimination in farm work. Huerta also encouraged entire families to get involved in the movement, because often entire families were doing the agricultural work.

Through the years, Huerta has also advocated for more participation in public life by women and people of color. She traveled around the U.S. encouraging Latinas to run for office as part of the Feminist Majority Foundation’s 50/50 by the Year 2000 campaign and served as National Chair of the 21st Century Party, which focuses on ensuring that political representation matches the makeup of America through gender and ethnic diversity.

Fighting for Agricultural Workers and the Working Poor

The through-line in Huerta’s life of activism has been farm workers. Although she lived with her mother after her parents divorced, her father was a farm worker and later a state representative. With César Chávez and the UFW, she has improved the lives of agricultural workers by helping them organize and fight for better pay and protections. Currently, she and her foundation continue to help farm workers by educating them about their rights, the laws and agencies that protect them, and the benefits and services they have access to.

Of particular importance to Huerta is farm workers’ ongoing exposure to dangerous pesticides. In addition to fighting low pay, long hours, and lack of healthcare, Huerta spoke out against the physical damage from exposure to pesticides she witnessed among farm workers, including cancer and birth defects. Although farm workers have had victories on this front, in a 2017 interview with NPR, Huerta said the fight is not over:

“This is a really, really big issue to this day for farmworkers. Because even though we were able to get many of the pesticides banned, they keep inventing new ones.”

In particular, Huerta mentioned chlorpyrifos, which the EPA failed to ban in 2019 despite evidence of links between exposure and severe health problems and birth defects.